Retirement Reality Check: Are Your Current Savings Sufficient For Retirement?

Saturday, May 10 2025 9:00 am

By Stephen Omojong, Research & Product Development Manager, NSSF Follow on LinkedIn

The foundation of social security is based on the recognition of the vulnerability faced by workers once they are no longer able to earn an income. The International Labour Organisation (ILO) conventions bring this out clearly by recommending protection for workers through the social protection floors embodied in the ILO Convention 102 and other derived resolutions and principles thereafter. In this article, we focus on the adequacy of savings.

This topic is motivated by the observed trends of pension schemes in East Africa, increasing contribution rates; Kenya and Rwanda both increased contributions to their mandatory retirement saving schemes, of NSSF and RSSB, respectively.

For many people in Uganda, retirement is a foreign concept, due to the large informal sector, which many people consider as “self-employment”. In essence, a self-employed person does not retire due to age. This is a myth that requires further interrogation. For now, however, we will address ourselves to the general expectation that every working person today will retire someday, as long as God blesses them with a long life. If people will retire, then they will need a source of income during retirement to survive on long after the monthly, daily or weekly wages run dry.

The eminence of retirement among other contingencies that stop or reduce a worker’s income is the reason why social security schemes and programs exist worldwide. While it is easier to come to terms with the fact that retirement will come for everyone lucky enough to live long enough, the question of how well to prepare for that time is less obvious.

There are two main strategies people use when planning for their survival in retirement – investing in assets which will give one sufficient cash flows, or maintaining membership in a social security scheme which offers one an assured pension in addition to an income-generating venture. The latter is the least risky retirement option, and is offered by Define Benefit Schemes, however, only one exists in Uganda – the public service pension scheme covering civil servants who are about 661,935 (excluding Uganda People’s Defence Force (UPDF), Internal Security Organization (ISO), External Security Organisation (ESO) and parastatals) out of a total labour force of just over 9.9 million. This implies that for most working Ugandans, their retirement is hinged entirely on how much they save or invest in long-term value-preserving assets today.

Therefore, how much must one save to assure oneself of a comfortable retirement? The simple answer to this question is to save as much as you can for your retirement. But that’s cliché and rather unhelpful. The correct answer cannot be arrived at without first finding out a few facts about what influences how much one will need in retirement, as a way of knowing how much then, one must save now. The amount one will need in retirement depends on what lifestyle they plan to live then. Most models assume that a typical retiree is likely to continue living a life similar to the one they lived while they worked, but toned down in a few areas.

For example, a retiree may not need to commute from home to the office every day, reducing the expenses related to that. They may choose to live in a retirement-friendly neighbourhood, e.g. relocating to a country home, and may adjust wardrobe expenses and social networking expenses among other work-influenced expenses. It can also be assumed that the retiree will have reasonably less dependents to take care of and should have paid off all debts by the time they retire. Retirees will not need to save for retirement anymore and may be exempt from income tax if they invest in a dedicated retirement asset like a pension account. However, while the retiree is expected to spend less in some areas, they are expected to spend more on others, such as health care and other services, which may have been accessed free of charge or cheaply courtesy of their employment perks.

The second question relates to whether the retiree plans to survive as a single person or if they plan to retire and live together as a couple. This question is relevant where a couple has both partners working and therefore both can contribute towards their retirement income. This implies that as individuals, they would need to each save a little less than people planning to retire as single individuals, regardless of the cause.

The third question relates to whether the retiree already has another source of retirement income financed outside the retirement savings, e.g. transfer income from children, income from assets already in one’s possession and any such reliable long-term income. Possession of such income reduces how much one would need to save now, while absence implies a requirement for a higher saving rate.

Other questions relate to time, that is, how long one has to work, when they hope to retire, and therefore how long they can save before they have to rely on the savings for post-retirement survival. This affects three variables. First is the amount one will be able to save up in the period they have. Second is the ability for their savings to compound over time if they are saved in an interest-earning account (which every long-term saver must do to guard against erosion of value due to inflation). Third is how long you will have to survive off the providence of your savings; this is rather subject to natural exogenous factors, but can be estimated based on life expectancy and life tables. A long saving period implies a less aggressive saving regime, and a long post-retirement period requires one to build a stronger and bigger post-retirement chest.

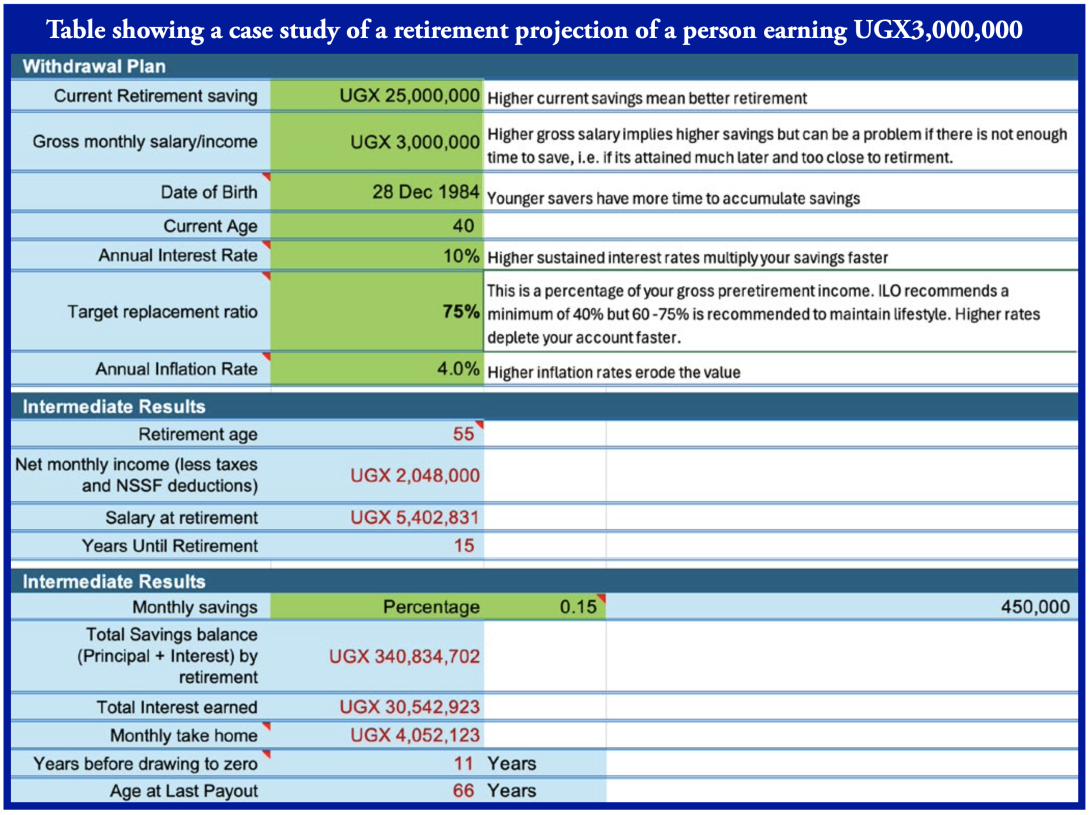

After considering the above personal factors, we can take an informed guess about the income a retiree will need and work backwards to deduce how much they need to save now. This method uses the income replacement ratio, which is a measure of what percentage of preretirement income you will need to maintain your preretirement lifestyle. For example, if you currently earn a gross income of UGX 3,000,000 and retire tomorrow, a replacement ratio of 75% would imply that your monthly retirement income is Ugx 2,250,000 (75% of 3,000,000).

ILO’s Convention No. 102 sets a minimum standard of 40% replacement of pre-retirement income for pensions. The ILO also emphasises that the ideal replacement ratio for retirees is 75% or higher to maintain their pre-retirement lifestyle, while www.moneyweb.co.za recommends a ratio between 70% and 80%. The logic behind the 75% recommendation is based on the expectation that, post-retirement, retirees don’t have to pay income taxes and do not have to continue incurring pension saving deductions. Those two waivers account for 25% of someone’s gross income in most countries. However, in Uganda, the average income tax rate (PAYE) is 30%, whereas the social security savings deductions are 5%. This implies that, following the same logic, a replacement ratio of 65% can match one’s preretirement net take-home.

Let us assume a saver hopes to have a preretirement income of Ugx 3,000,000, and their net income is Ugx 2,048,000 after PAYE and NSSF deductions. We are going to assume a replacement ratio that maintains a retiree’s take-home, which is 68%. With this replacement income in mind, we can use the examples below to visualise the saving target for the different profiles of savers.

Download the tool here.

Key notes about the tool:

The main determinants of sufficiency of one’s monthly take-home in retirement are: how much one has saved, interest to be earned on the savings, age of the saver and therefore how long their money will compound, as well as their saving rate. When savers save more for longer periods in high-interest-earning accounts, they stand a better chance of replacing their preretirement income.

In this example, the saver has UgX 25 million in their retirement account, they earn a net income of UGX 2.04 million from a gross of UGX 3 million while saving 15% of their gross salary each month. Being 40 years of age implies that they have 15 years of saving and compounding of interest before they can draw from their retirement account. In that period, they will be able to grow their savings from the current 25 million to 340 million thanks to interest compounding and the additional savings.

We note that despite the growth in deposits, the preretirement income/salary also increased over time, now requiring a higher monthly take-home from the savings account to maintain the member’s lifestyle at current prices. This strains the savings and can only support the member for 11 years until they are 66 years old. When members find themselves in this situation, they would have to sacrifice some elements of their lifestyle to reduce the monthly take-home to prolong the drawdown period rather than running out of retirement funds early.

Key assumptions

Salary increments are solely based on inflation. Inflation is constant throughout the projected period, and so is the return on one’s savings. We also assume that savers do not make unscheduled withdrawals or deposits from or into the accounts, respectively. Unscheduled deposits improve the replacement ratio, while drawings like midterm withdrawals worsen the post-retirement income situation.